Russian Insulator Report, 1994

by Donald M. Fiene

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", November 1994, page 15

Against all odds, I managed to squeeze in one last trip to Russia before I

retire in 1995. I gave a number of lectures on icons at a seminar in Moscow from

June 11 through June 26. All my expenses were paid, plus I got a big check

besides. It was basically the National Endowment for the Humanities that

financed it, so you might want to write to your congressman and see if he (or

she) thinks your tax dollars are going in the right direction.

The Russians are

in a bad way. Inflation has increased so rapidly that all of their coins are

worthless. Only the highest value coin -- the 300 rouble -- may be said to have any

value at 14 cents. Meanwhile, paper hardly does any better. During the time I

was in Moscow, it took 2100 roubles to buy what a dollar buys. Ten years ago the

rouble and the dollar were officially equal. In those days the highest paper

note was 100 roubles. Today it is 50,000 roubles -- and that amount buys only about

$25 worth of stuff. Everybody's pockets are full of worthless colorful paper.

Subway tokens -- made of plastic -- had been set very low (100 roubles), but two days

before I left the price jumped to 150 roubles -- reflecting another major

inflationary rise throughout the country. The food at our hotel was not too bad,

except that we were served liver at least three times a week. Bad scene! It was

depressing watching the Russians suffer. I was glad to leave for that reason. I

should mention also that the temperature was in the forties almost every

morning. You could see your breath some days.

As far as insulators are

concerned, I did manage to find three good ones. To put these in a proper

context, see my last two articles on Russian insulators in Crown Jewels of the Wire of November, 1989,

and December, 1992. The latter article indicates that on my return to Russia I

would search for a nine inch diameter, three-skirt glass power insulator, of amber

color -- visible overhead on the electric commuter-train power poles, but

nowhere else. These insulators were located on the lines going west from the

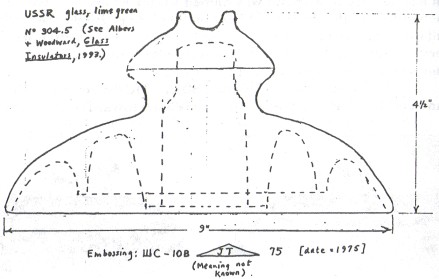

Kiev train station. I later noted that this glass type was listed in Glass

Insulators from Outside North America, Second Revision, by Marilyn Albers

and N. R. Woodward, 1993, with a CD number of 304.5. (I believe only one

example, damaged, and in a lime-green color, was known to the authors.) This

insulator is of interest for its size: no other three-skirt insulator in

this style, glass or porcelain -- has a diameter so great.

I had learned in 1992 that the third and fifth stations on the "elektrichka" (Ochakovo

and Solnechnaia) had "energy sections:' or energo-uchastki associated with

them -- that is, electrical substations, racks of telephone poles, piles of

discarded insulators, huge bins of new "isoliatory," and so on. As

soon as I got settled in Moscow in 1994 I took a little trip on the suburban

train, but not without difficulty. There were dozens of tracks going west, with

trains pulling out continually. I had trouble reading the timetables and was

never really certain where all these trains were going. In response to my

queries I would get a dozen different answers. And the trains were hideously

crowded -- like those in India in the 1940's. Still, they were cheap -- about 50 cents

for the first 20 miles. (One of the last vestiges of socialism.) Finally I

leaped onto a platform just as the train was pulling out. My fellow travelers

assured me that the train stopped at Solnechnaia -- the station I had decided to

investigate first.

Because of all my fooling around, I did not arrive at

Solnechnaia until almost quitting time. I had to climb over two walls to reach

the uchastok just as all the workers were leaving. But one stopped to listen to

me. He liked the pictures of my collection that I showed him. He unlocked the

door and offered me a seat. He said Solnechnaia, where he worked, was no good --

no

glass insulators at all. He quickly called two other sections, making contact

just before the last person had left for home. "The best place for

you," he said, "is Vnukovo. They're loaded." He drew me a map and

wrote down a couple of phone numbers. I thanked him and took the next train

back to the city.

A week later I had a free morning. I took the elektrichka to

Vnukovo (two stops past Solnechnaia) and tracked down Uchastok No.9. I asked to

see the boss. The latter turned out to be a nice old guy who had just retired at

age 66 and kept on coming in to work because he had nothing better to do.

Meanwhile, I myself was a harmless old geezer who would retire within a year at age 65. My

new friend was named Viktor Kharikov -- who had actually been the director of

Section 9 before retiring. We walked all over his territory looking for amber

glass power insulators -- and never found the first one. There were plenty of heavy

brown porcelain types, but I was not interested in those.

|

|

|

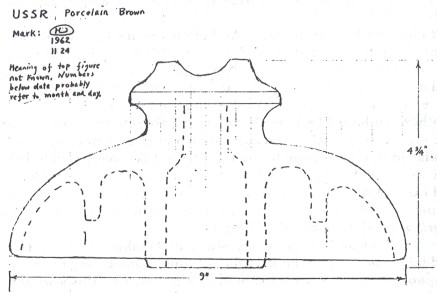

CD 304.5, light green and nine inch diameter brown porcelain |

So we returned to

Viktor's office. He did some telephoning and decided that Ochakovo, four stops

back toward town, was the best place for big power glass. And to make sure I got what I wanted, Viktor

came along with me. By this time I had little hope of getting the amber

insulator. Nevertheless, Viktor was able to find a replica of it in green. It

had been lying in the tall grass at one end of the yard, was in mint condition,

and there was not another insulator like it on the premises, Or rather, there

was just one --- a brown porcelain insulator nine inches in diameter, very similar

in size and shape to the CD 304.5. I decided to keep this. The third insulator I

decided to keep was a combination of glass and iron, rather heavy. It turned out

to be very similar to one I found in Armenia in 1985. (See the illustration on

page 14 of Crown Jewels of the Wire, December 1985.)

Viktor and I said our

farewells at Ochakova station. He said he would keep on looking for the amber

glass; he gave me his telephone number in case I should ever get back to Moscow:

280-7814. He also wrote me a note authorizing me to possess three secondhand

glass objects. That was for customs.

As it turned out, the note came in handy.

The customs official, as soon as he saw my glass and iron on his radar screen,

immediately demanded that I open my suitcase. "What are these?" he

wanted to know. "Isoliatory," I said. "What???" he said. But

I showed him the note and I flashed through the photos of my collection.

"Now I understand," he said. He was all smiles. He waved me through.

So I did it again. This visit to Russia was my thirteenth -- no less lucky than

the others. I'm only sorry that I won't be going again. I have brought back well

over 100 insulators from the USSR since 1966, eight of which I have kept in my

collection.

|